Developed in the late 1940s, acrylic paint has only a brief history compared to other visual arts media, such as watercolor and oil. Polymer-based acrylic entered the market as house paint, but its many benefits brought it to the attention of painters. By the 1950s, artists began using quick-drying acrylic to avoid oil paint’s considerable drying time. These artists found that the synthetic paint was very versatile and possessed much potential. As time passed, manufacturers improved methods by formulating artistic acrylic paints with richer pigments. Although it has proven versatile in artistic endeavors, acrylic as a medium is still in its infancy.

For many contemporary artists, acrylic became the perfect vehicle to drive their crafts. Offering a range of possibilities, acrylic can produce both the soft effects of watercolor paint and sharp effects of layered oil paint. In addition, acrylic can also be used in mixed media works, such as collage, and its versatility lends itself to experimentation and innovation. Acrylic does have some limitations. Its quick-drying plasticity discourages blending and wet-on-wet techniques, therefore creating boundaries for artists. Still, those who embraced acrylic in their work created fresh, new approaches reflecting all that this medium can offer.

Pop artist Andy Warhol explored acrylic’s range of effects. His famous “Campbell Soup Can” demonstrates the sharp, bold clarity possible with acrylic, while the stark and eerie “Little Electric Chair (Orange)” shows the grim subject in a faded and almost gentle light. Other artists’ works also demonstrate the possibilities of acrylic. In David Hockney’s “Three Chairs with a Section of a Picasso Mural,” acrylics provide the softness of watercolor, while in “Rocky Mountains and Tired Indians,” they create a sharpness similar to oil paints. This is not to imply that acrylic works should be viewed only in terms of other media. Acrylic is its own medium with its own possibilities.

Robert Motherwell used acrylic with pencil and charcoal to achieve striking effects, and contemporary Op artist Bridget Riley also took advantage of its ability to set easily on support mediums, such as wood, canvas, paper and linen. Mark Rothko’s series of untitled acrylics, on both canvas and paper, demonstrate its ability to enhance formal elements, such as tone, depth, color and scale. His colorfield paintings allowed audiences to approach the medium on its own terms. Acrylic’s future as a medium continues to unfold with each new work by the skilled hands of artists. Perhaps its full potential and possibilities have not yet been developed. However, it is clear that acrylic is an important medium, demonstrating the continual power and evolution of visual art.

Miami Artist Asif Farooq Kicks Heroin Habit, Makes Cardboard Weapons →

Asif Farooq stooped over a metal sink in a Jackson, Mississippi Huddle House restaurant. Feverishly scrubbing away at the mountain of pots and dishes in front of him, he tried to wash away his doubts about whether he'd finally found a way to kill his 20-year heroin addiction.

"I constantly fell asleep, and threw up on a girl in my math class."

It was 2010, and Farooq was in the final stages of a seven-month stint at the nearby Caduceus Out-Patient Addiction Center (or COPAC), a rural 23-acre facility for hard-core addicts. Farooq had been in similar spots before, and every time, his addiction had returned. But this time, the thought of a relapse made him angry.

"The patients at COPAC all believed I was the first one who was going to start using. It angered me. I thought the most rebellious thing I could do was not get high," the 34 year-old artist says today.

The Kendall native found one way to make that rehab stint different. To cope with the tedium of group therapy sessions, the stifling hours alone, and the homesickness, he'd begun making eerily realistic revolvers and pistols out of cardboard. He had to fight the center's bosses to get the materials he needed.

"Like any good junkie, I had a list of demands that included being allowed to use razor blades or the X-Acto knives and glue I use to make my guns," he says. "Luckily, they accepted and allowed me to work on my art in my free time."

He gave the guns as gifts to fellow patients, but when he returned to Miami in December 2011, the pieces opened new doors for him in the fine art world. Miami's Primary Projects caught onto the AK-47s and AR-style assault rifles carefully sculpted from used Cinnamon Toast Crunch cereal boxes and other trash and gave him a breakout show during Art Basel 2012.

Now, as 2014 begins, Farooq is one of Miami's most inspiring art tales — a talent with a unique vision that promises to make bigger waves this year with everything from a full-scale fighter jet made from cardboard to plans to transform Primary's full space into a twisted turn-of-the-century hunting milieu.

"People have no idea how talented Asif is," says Primary Projects' cofounder and artist Typoe, who, along with his partner BooksIIII Bischof, is planning exhibits with Farooq. "He is unlike any other artist I have ever known. His mastery of his craft — everything from glass blowing to welding and engineering — obsession with precision, and enthusiasm for his work are mind-blowing."

Farooq was born at Baptist Hospital and grew up in a quiet Kendall suburb in a middle-class home with his mother and father, who migrated here from Pakistan and Afghanistan. His father, Dr. Humayoun Farooq, was a civil engineer who worked for Miami-Dade County before starting his own business in the late '70s. Farzana, his mother, was a homemaker who later took over the family engineering firm when Farooq's father died of cancer five years ago.

Farooq says his parents placed a high value on education. "My father used to sit with me after school for several hours working on math and science problems after I finished my regular homework."

Farooq's siblings all went on to become professionals, but the insatiably curious Asif always felt like an outsider. "I was that skinny brown kid with the bifocals that teachers lumped with the three Korean girls," he says.

In fourth grade at South Dade's Gateway Baptist Elementary, Farooq found the artistic streak that would become his calling. "Instead of doing my assignment, I was drawing a picture of a Lamborghini Countach when the girls next to me and even some boys who never paid me attention started huddling to see my picture."

Not long after that transformative moment, the drug problems that would torment Farooq throughout his artistic career surfaced. He was kicked out of Glades Middle School for alleged drug abuse. Farooq denies he was using then but says he soon began taking drugs to spite the authorities who'd expelled him. By the time he was a freshman at South Miami Senior High, drugs were a regular part of his life.

"I constantly fell asleep, and threw up on a girl in my math class," he recalls. "Once I got into the powders — cocaine and heroin — that's when I dropped out of school and things became different."

Even as his school life was falling apart, Farooq's talent was still evident. At 15, he showed up at the Metal Man Scrap Yard near the Miami River to try his hand at sculpture. "It was run by a former Army staff sergeant... who encouraged me to weld bits of metal together as long as I took it all apart when I finished," Farooq recalls.

Farooq, who'd earned a GED after leaving high school, enrolled at Miami Dade College and later attended the Art Institute of Chicago. But he was booted from the school for forging an ID. "I never asked why it happened, and they never told me, and that was that," Farooq says. "I was into a lot of bad shit back then."

Back home in Miami in his early 20s, unemployed and with few prospects, Farooq spent close to a decade struggling with addiction, bouncing in and out of jail and rehab programs and building and repairing synthesizer keyboards for local musicians.

In the spring of 2009, he found himself at South Miami Hospital with a heart infection caused by a dirty needle. Laid up with a potentially fatal condition, Farooq began keeping a diary in which he scribbled plans for building an airplane. After he was released from the hospital, he moved to Mississippi to enroll in the rehab program and soon began making the cardboard weapons that would become his trademark.

When he returned from Mississippi, he contacted Miami artist Typoe, one of the founders of Primary Projects, who was bowled over by Farooq's sculptures and got him into a group show called "Champion." At the exhibit, Farooq displayed a full-scale hand-crafted cardboard rendition of a 1930s DShK Soviet heavy machine gun. Farooq titled the imposing work Countach to honor what he recalls his genesis moment.

"It's a Piedmontese Italian slang expression that roughly translates to 'oh shit,'" the artist says. "As the story goes, workers at the Milan auto show uttered this expression upon first seeing the Lamborghini that would eventually go by that name. It's the same car I drew up in... class that day, and it's what I named the DShK sculpture all those years later because everyone would say 'oh shit' when they saw it."

The show landed Farooq a spot during Art Basel 2012 with Primary Projects, where his exhibit "Asif's Guns" was a pop-up store in Wynwood featuring 300 firearms, ranging from revolvers to rifles, crafted with uncanny precision. The display took 7,000 hours of labor, with Farooq's friends and family chipping in while he toiled away in his mother's garage. His fake guns flew off the shelves, with revolvers commanding $300 and rifles $2,000, each priced the same as the real McCoy, as 40,000 visitors elbowed through the doors.

Today, Farooq is working on several large-scale projects for Primary, including "War Room." Due to be finished this summer, the exhibit will turn the gallery into a Napoleonic-era country gentleman's estate, replete with musket rifles, dueling pistols, and other weapons of the age.

In his modest Kendall studio, Farooq is pursuing his biggest dream. He's quietly building a full-scale Polish MiG-21 fighter jet employing 200,000 parts, including a cockpit that spectators can climb into and retractable landing gear. He expects his supersonic opus to debut in early 2015.

"Anything worth having is worth working hard for," Farooq says. "One thing I learned at COPAC and in the years after is restraint. [In 2013] I could have made more money with my art than I have ever earned, but I'm glad my gallery directors are intelligent enough to allow me to develop and have been so supportive of the work."

Farooq has been inundated with invitations to show his work outside Miami and was asked to lecture on art at the University of Arkansas next spring. All it takes are the memories of Mississippi to remind him that his biggest goal is one that begins every morning, though.

"Right now my main focus is building my airplane," the artist says. "But you can say my real dream is to die clean."

10 Tips for Choosing Artwork for Your Home →

1. Buy Art that You Love. Whether or not it has the potential to rise in value, it should be something you will enjoy having in your home every day. Remember, the art is for you.

2. Be Open to Different Mediums. Why always pick a painting? Find the type of art that will work best for your space. Paintings will add a broader swathe of color. Sculptures will add depth to the room, and mixed media pieces add texture or a mixture of visual elements. Which medium will have the greatest impact on enhancing your room’s decor?

3. See What’s Out There. Get out and see the art being exhibited in your area. Great local and original art is displayed everywhere from coffee shops and colleges to galleries and restaurants. If you can’t find a piece thats the right size or with matching colors from a local source, a quick search online should direct you to affordable art that matches what you need.

4. Pick the Right Size. Measure your wall’s dimensions and bring pictures of the room with you. That way, when you are out looking at art, you will have a better idea of what space you have to work with and can imagine how the art will look in your home.

5. What’s the Focal Point? A room can have more than one area that draws your attention. Are you looking for a single point that will define the room, or some decor pieces to complement your overall color scheme? Make sure all the room’s design elements have some breathing space to avoid a cluttered look.

6. Color is key. Pick artwork that contains some of your room design’s more attention grabbing colors. A piece with similar or complementary colors can work great as well. Take into account your wall color, furnishings, pillows, throws and curtains to create a palette of colors to look for in your artwork.

7. Content Matters. What does the artwork depict? Do the waving lines in the painting mirror your curved coffee table? Does the tropical pattern of your upholstery reflect the theme of the painting? Depending on the mood and shapes in the work, select imagery that will harmonize best with the room's contents.

8. Or Does It? A traditional interior does not always require traditional artwork. A showstopping contemporary piece can make an impressive statement above a mantle in a traditionally styled living room. Sometimes a contradiction is exciting and new. Think outside of the box.

9. Hang it right. Make sure the artwork is hung at the correct height. It should be approximately eye level. Try following the art gallery standard, which means the center of the painting should be about 60 inches from the floor.

10. Light it Up. The importance of lighting your artwork can not be overemphasized. Dimly lit artwork will lose impact and look dull and muted. Great lighting will make your artwork pop and contribute to the mood of the room.

Art Nouveau Movement →

Image via Deviant Art

Art Nouveau was a movement that swept through the decorative arts and architecture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Generating enthusiasts throughout Europe and beyond, the movement issued in a wide variety of styles, and, consequently, it is known by various names, such as the Glasgow Style, or, in the German-speaking world, Jugendstil. Art Nouveau was aimed at modernizing design, seeking to escape the eclectic historical styles that had previously been popular. Artists drew inspiration from both organic and geometric forms, evolving elegant designs that united flowing, natural forms with more angular contours. The movement was committed to abolishing the traditional hierarchy of the arts, which viewed so-called liberal arts, such as painting and sculpture, as superior to craft-based decorative arts, and ultimately it had far more influence on the latter. The style went out of fashion after it gave way to Art Deco in the 1920s, but it experienced a popular revival in the 1960s, and it is now seen as an important predecessor of modernism.

- The desire to abandon the historical styles of the 19th century was an important impetus behind Art Nouveau and one that establishes the movement's modernism. Industrial production was, at that point, widespread, and yet the decorative arts were increasingly dominated by poorly made objects imitating earlier periods. The practitioners of Art Nouveau sought to revive good workmanship, raise the status of craft, and produce genuinely modern design.

- The academic system, which dominated art education from the 17th to the 19th century, underpinned the widespread belief that media such as painting and sculpture were superior to crafts such as furniture design and silver-smithing. The consequence, many believed, was the neglect of good craftsmanship. Art Nouveau artists sought to overturn that belief, aspiring instead to "total works of the arts," the infamous Gesamtkunstwerk, that inspired buildings and interiors in which every element partook of the same visual vocabulary.

- Many Art Nouveau designers felt that 19th century design had been excessively ornamental, and in wishing to avoid what they perceived as frivolous decoration, they evolved a belief that the function of an object should dictate its form. This theory had its roots in contemporary revivals of the gothic style, and in practice it was a somewhat flexible ethos, yet it would be an important part of the style's legacy to later movements such as modernism and the Bauhaus.

Art Nouveau (the "new art") was a widely influential but relatively short-lived movement that emerged in the final decade of the 19th century and was already beginning to decline a decade later. This movement - less a collective one than a disparate group of visual artists, designers and architects spread throughout Europe was aimed at creating styles of design more appropriate to the modern age, and it was characterized by organic, flowing lines- forms resembling the stems and blossoms of plants - as well as geometric forms such as squares and rectangles.

The advent of Art Nouveau can be traced to two distinct influences: the first was the introduction, around 1880, of the Arts and Crafts movement, led by the English designer William Morris. This movement, much like Art Nouveau, was a reaction against the cluttered designs and compositions of Victorian-era decorative art. The second was the current vogue for Japanese art, particularly wood-block prints, that swept up many European artists in the 1880s and 90s, including the likes of Gustav Klimt, Emile Galleand James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Japanese wood-block prints contained floral and bulbous forms, and "whiplash" curves, all key elements of what would eventually become Art Nouveau.

It is difficult to pinpoint the first work(s) of art that officially launched Art Nouveau. Some argue that the patterned, flowing lines and floral backgrounds found in the paintings of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin represent Art Nouveau's birth, or perhaps even the decorative lithographs of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, such as La Goule at the Moulin Rouge (1891). But most point to the origins in the decorative arts, and in particular to a book jacket by English architect and designer Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo for the 1883 volume Wren's City Churches. The design depicts serpentine stalks of flowers coalescing into one large, whiplashed stalk at the bottom of the page, clearly reminiscent of Japanese-style wood-block prints.

Quote of the Week: Henri Matisse

“Creativity takes courage. ”

Studio Visit: Deborah Hill

Laughing Crow Interior

August at studio and boxer adoption

Molly and Moose at the studio

The artist is from the Appalachian foothills of Alabama, she has been in Texas since 1992 and currently maintains a studio in Cypress, Texas.

To see more of her work visit the gallery or check her website here

Public Art Installation at NorthPark Brought To You By San Francisco Artist Jim Campbell →

Jim Campbell's “Scattered Light" installation, originally commissioned for Madison Square Park in NYC in 2010, is coming to the outdoor garden at NorthPark Center in Dallas.

NorthPark's manicured CenterPark Garden will play host, starting November 25, to this very popular outdoor installation, which most recently appeared in Hong Kong. It's made up of 1,500 suspended LED lights that look like old-school incandescent bulbs, which are staggered and programmed to blink in such a way as to animate a moving image of human shadows walking across and through the light field. Here's a link to a short video to better illustrate what I mean. It's pretty cool.

By photos posted online of its previous installations, it looks as though viewers are also invited to walk and sit among the lights.

The installation will go up in time for the holiday season but stay at NorthPark through the spring. NorthPark, known for its architecture and art displayed throughout, was built by the Nasher family and showcases work from the Nasher collection (and visiting public work) with a program independent of the Nasher Sculpture Center.

This post originally appeared on Glasstire, on Thursday, November 13, 2014.

How to Choose the Right Brush for your Art →

A carpenter must understand how to use his or her own tools in order to build a house, so must an artist know how to use his or her tools to paint a successful painting.

At first, knowing how to choose the right art paintbrush is a daunting task.

The material that the paint brush hairs are made of, how they are bunched together, their length and shape all affect the characteristics of the brush.

Here is a list of the duties of some of the most popular brush shapes:

Square: A squared-off brush.

Flat:

- Brush length twice as long as width

- Use for backgrounds and details.

- Use for covering large areas

- blending

Bright:

- Width equal to length Allow for the most control

- Great for coverage

- Blending

Filbert: This brush is similar to a flat but has has a round outer edge.

- The Filbert’s shape can vary from a flatter brush with a rounded outer edge to an oval shape.

- The Cat’s Tongue shape comes to point for more control.

- A multi tasking painting brush.

- This brush can take the place of a round or flat depending on the way the artist holds the brush.

Round Brushes: Primarily used for detail and working in small spaces.

Standard Round:

- Use for shaping, details, and outlining.

Pointed round:

- Use for retouching, finishing touches and details.

- Pointed tip for coloring.

- With a high reserve, this brush is widely used for watercolours

- Worn rounded:

- Avoids “rounding”.

Script, Liner & Detail: All three brushes are similar and used for painting fine lines. They can all be used for lettering, animal whiskers, branches, and artists’ signatures.

- Script:

- The longest hair tufts.

- Holds the most paint.

- Liner:

- The mid length hair tufts.

- Compromises between fine detail and longer flowing strokes.

- Detail:

- The shortest hair tufts

- Offers the most control

Fan: Fan brushes used for shading, blurring and glazing.

- The Fan paintbrush is a thin layer of bristles spread out

in the shape of a fan. - Fan brushes are generally used for blending and feathering colors.

- Fan brushes can be used for painting trees, branches, grasses and detail.

- It is popular for painting hair with its ability to paint multiple flowing strands in a single stroke.

Mop: Like the name says, these brushes allow you to ‘mop’ up a lot of paint.

- Usually larger brushes favored by watercolorists, but also used with oils and acrylics.

- Used for making large washes.

- Used for blending and shading with oils.

Famous Artists: Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986) →

Image via Google

Georiga O'Keeffe

Born on November 15, 1887, in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, Georgia O’Keeffe was a female artist and icon of the twentieth century. She was an early avant-garde artist of American Modernism. Her life spanned 98 years, and her portfolio includes many works of American landscapes. She received early art instruction at the Art Institute of Chicago (1905-1907). In 1907, she moved to New York City and studied under William Merritt Chase as a member of the Art Students League. Her early career led her to further studies at Columbia University Teacher’s College and educational posts at the University of Virginia and Columbia College.

In her New York years, O’Keeffe created works described as examples of avant-garde Modernism, abstract, Minimalist, and color field theory. Two of her paintings demonstrate her lifelong skill with color regardless of the subject matter. In 1919, O’Keefe created “Blue and Green Music” and became prominent with support from Alfred Stieglitz. This abstract piece is a beautiful work of rhythm, movement, color, depth, and form. She echoes this work again in 1927 with “Abstraction Blue.” When O’Keeffe painted in watercolor or oil, she also captured beauty and emotion. In later works, O’Keeffe continued this tradition, including famous pictures of flowers and New Mexican landscapes.

O’Keeffe developed a powerful relationship with the wealthy and famous photographer, Alfred Stieglitz. The two were quite a power duo. Stieglitz is remembered as the first photographer to be exhibited in American museums, the power behind Modernist artists with his gallery 291 in New York City, the person who brought Modernism (ala Picasso) to America, and an artistic influence on artists like Ansel Adams. Although their friendship began in 1917 while Stieglitz was still married to his wife, O’Keeffe married Stieglitz in 1924.

When Stieglitz died in 1946, O’Keeffe moved from their home in Manhattan’s Shelton Hotel to New Mexico. She divided her time between a home called Ghost Ranch (frequented since the mid-thirties and purchased in 1940) and a Spanish colonial at Abiqui (purchased in 1945 and occupied in 1949). In her “Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II” (1930), O’Keeffe again depicts movement, beauty, volume, and depth, especially in brilliant blue forms of New Mexican mountains. O’Keeffe’s work reflected other travels and influences, including a friendship with the Mexican artists, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s cultural impact is preserved by the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico. This museum offers the only research center in the world devoted to scholarly study in American Modernism. A visit to this museum or another venue where her work is shown suggests why she was the first woman to have a solo exhibition in 1946 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. O’Keeffe died on March 6, 1986.

Introduction to the Artistic Style of Conceptual Art →

Image via Google

Beginning in the 1960s, conceptual art was described as anti-establishment. First, picture the commercial images of Marilyn Monroe popularized by Andy Warhol. Realize that some artists were opposed to the concept of getting rich through commercial art sales. Conceptual artists wanted to make the masses think instead of giving them plastic art to consume.

As a movement, conceptual art creates disharmony in society, jarring people out of their traditional understanding of art. According to the “Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,” “Conceptual art, it seems, is something that we either love or hate.” A piece of conceptual art challenges the viewer to defend the work as a true piece of art instead of something masquerading as art. Thinking about the artist’s deeper meaning in a conceptual art piece helps the viewer understand an important statement about society.

George Brecht (1926-2008) was the son of a flutist for the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. In 1961, Brecht performed his conceptual art piece entitled “Incidental Music.” This performance art can only be described as Brecht stacking up toy blocks inside a grand piano. In his obituary, George Brecht was described as a “provocateur” by the “New York Times.” He belonged to an international collection of artists called the Fluxus, mainly conceptual artists like him. Brecht died at the age of 82.

A different consideration is the artist Joseph Kosuth (b. 1945). His composition, “One and Three Chairs” (1965) consisted of a plain, beige wood chair sitting next to a life-sized photograph (black and white) of a wood chair. Taken out of historical context, “One and Three Chairs” does not appear to be art at all. However, taking something as plain as a chair captured on photo paper and positioning it next to a real chair suggests simplicity or absurdity depending on your point-of-view.

The peak of conceptual art occurred from 1966 to 1972. Artists reacted to the art critic, Clement Greenberg’s narrow definition of Formalism. According to Honour and Fleming (2005), Greenberg “saw the art object as being essentially self-contained and self-sufficient, with its own rules, its own order, its own materials; independent of its maker, of its audience; and of the world in general.”

Even the artist, Marcel Duchamp, a young friend of Dadaism and Surrealism decades earlier, created a piece of conceptual art in the final twenty years of his life – “Given: 1. The Waterfall 2. The Illuminating Gas.” This piece included part of a nude woman made of leather and other pieces of found art. The viewer had to look through a peephole to see this shockingly erotic composition. In “Given” (1968), Duchamp bridged the thirty-year chasm between Surrealism and conceptual art. While conceptual art occurred in the U.S. in the context of civil rights, the same movement abroad bucked all of the traditional notions of the art establishment.

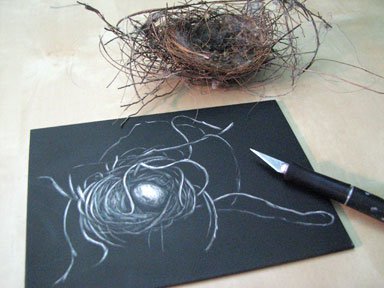

What is Scratchboard? →

The term scratchboard refers to the surface. A scratchboard (aka scraperboard or scratchpaper) is a surface which has been coated with a layer of white clay. This backing can be a hard board (masonite) or a thin paper. I use a scratchboard made by Ampersand — it is prepared on a masonite board, so it does not bend or crack and the layer of clay is thicker than on paper. Scratchboard can be purchased with just the smooth white clay surface or prepared with a layer of black ink.

The basic materials I use are black waterproof ink, a paintbrush, pigment pens, and a fine craft knife with a #11 blade. The above image shows a piece that was started on black scratchboard. These are the quickest as you can start scratching immediately.

Working a white clay surface requires a bit more patience as you have to wait for the ink to completely dry. This is the basic process when starting on a white clay surface.

1. Paint ink onto the surface in the outline of subject

2. Use a fine blade to scratch away the ink.

3. Continue scratching away details with the blade.

You can add other details with a fine black pen or brush.

Last year I wrote a demonstration article for Artist’s Palette Magazine about how I create a illustration on white clayboard. You can view a PDF of the article here.

Studio Visit: William N. Beckwith

B.B. King enlargement

L.Q.C. Lamar enlargement

Elvis enlargement

William N. Beckwith

is an Artist from Greenville, MS who now lives and works in Taylor, MS. He has produced public and private art for 30+ years. Check out more of his work in our Artist section and here

World's Biggest Art Collector Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al-Thani Dies at Age 48 →

Sheikh Saud Al-Thani, 2002.

Once widely regarded as the world's richest and most powerful art collector, Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al-Thani of Qatar died suddenly at his home in London on November 9, age 48. Details of his death have not been announced, although initial reports say it was from natural causes. A cousin of the Qatar's current Emir, Sheikh Al-Thani served as the country's president of the National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage, from 1997 to 2005. During his tenure, he oversaw the development of the oil-rich nation's ambitious plans to build an extensive network of new schools, libraries, and museums. He also spent well over $1 billion on art purchases during that period, more than any other individual, according to many art-market observers.

Qatar's royal family is known for its prodigious collecting habits, ranging from ancient manuscripts to contemporary art. Over the past two decades, Sheikh Al-Thani acquired a vast collection of art and artifacts, with a special concentration on historical pieces, including Islamic ceramics, textiles, scientific instruments and jewelry (see "Sheikh Al-Thani's Watch Sells for $24 Million After His Mysterious Death"). His collection makes up the bulk of holdings in five existing and planned museums: the Museum of Islamic Art, the National Library, the Natural History Museum, a Photography Museum, and a museum for traditional textiles and clothing.

Sheikh Al-Thani was also a major collector of vintage cars, bicycles, antique furniture, and Chinese antiquities. In 2005, he was dismissed from his post and circumstances surrounding his purchases and holdings were investigated. Relatives accused him of embezzling millions from family members and misappropriating public funds. He was cleared of wrong-doing shortly after, however, and returned to his position as a major player in the international blue-chip art market.

Oil Paint: The History and Development of a Medium →

As evidenced by the innumerable masterpieces exhibited on gallery walls of the most prestigious museums worldwide, perhaps it is the medium of oil that has created the most significant impact on the development of painting as visual art form. Painting with oil on canvas continues to be a favored choice of serious painters because of its long-lasting color and a variety of approaches and methods. Oil paints may have been used as far back as the 13th century. However as a medium in its modern form, Belgian painter, Jan van Eyck, developed it during the 15th century. Because artists were troubled by the excessive amount of drying time, van Eyck found a method that allowed painters an easier method of developing their compositions. By mixing pigments with linseed and nut oils, he discovered how to create a palette of vibrant oil colors.

Over time, other artists, such as Messina and da Vinci, improved upon the recipe by making it an ideal medium for representing details, forms and figures with a range of colors, shadows and depths. During the Renaissance, which is often referred to as the Golden Age of painting, artists developed their crafts and established many of the techniques that provided the medium of oil to emerge. The refinement of oil painting came through studies in perspective, proportion and human anatomy. During the Renaissance, the goal for artists was to create realistic images. They sought to represent all that was caught by an artist’s detailed eye, as well as capture and present the intensity of human emotions.

Giovanni Bellini’s work from 1480, “St. Francis in Ecstasy,” captures oil’s ability to create an accurate, complex composition with the soft glow of morning light and the detailed perspective of the natural landscape. Oil became a useful medium during the Baroque period, when artists sought to display the intensity of emotion through the careful manipulation of light and shadows. Rembrandt’s use of oil in his piece, “Night Watch,” from 1642, displays the concerns of the night watch with a dark, yet detailed background and the crisp brightness of the golden garments. In the mid-19th century, as painters explored new approaches and developed new movements, oil as a medium followed. In the 1872 painting “Impression, Sunrise,” for which the Impressionist movement was named, Monet used oil to provide an evocative view of the harbor, silhouettes and sun as reflections danced on the water. Into Modernism and beyond, oil has been used by artists, such as Kandinsky, Picasso and Matisse, to further their experimental approaches in the early 20th century.

Easily removed from the canvas, oil allows the artist to revise a work. With its flexible nature, long history and large body of theories, oil painting has created a most significant impact on visual art. New developments in oil paints continued into the 20th century, with advent of oil paint sticks, which were used by artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Anselm Kiefer. Since the Renaissance, the masters used oil to create works that continue to inspire, intrigue and delight, and today, artists continue to use this significant medium to express their visions, goals and emotions.