Within the context of art, a cityscape is a work that showcases aspects of cities. It is often known as the urban equivalent of a landscape. Cityscapes are reflected by such mediums as paintings, etchings, drawings, or even photographs. Cityscapes are differentiated by town or village scenes that are less urban in nature. Cityscapes reflect various aspects of cities including (but not limited to) buildings, urban parks, city skylines, and city streets.

The city in art has a long history. Some early works date to ancient Rome, for example. The Baths of Trajan, for instance, depict a bird's-eye view of the city. Cityscapes were also created during the Middle Ages; however, these works often served as backgrounds for views of portraits. By the seventeenth century, cityscapes became a celebrated genre of art, particularly in the Netherlands. A famed work from this era is the View of Delft painted by Johannes Vermeer between 1660 and 1661. Dutch cities like Amsterdam and Haarlem were also featured during this period.

During the eighteenth century, cityscapes became popular in many other European nations, especially in the Italian city of Venice. Some of the most celebrated cityscapes date to eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, groups like the Impressionists experimented with new techniques to showcase views of the city. The common thread between the various artistic genres in cityscape works is the representation of the city's physical aspects.

The cityscape as a popular genre declined considerably during the nineteenth century as more abstract and works of modernity took center stage. Even so, some modern artists continued to reflect the city in their works. A few celebrated painters like Edward Hopper continued to incorporate cityscape elements into their works. Some contemporary artists focus on the city as the subject matter of their art today. For instance, Stephen Wiltshire is known for his panoramic city views. The artist Yvonne Jacquette is celebrated for her aerial cityscapes.

The cityscape genre has been favored by many historic painters during their era such as Alfred Sisley, James McNeill Whistler, Childe Hassam, Giovanni Canaletto, and John Atkinson Grimshaw. While there is a plethora of world-renowned cityscape works collected by museums today, some particularly celebrated works include City by the Sea (c.1335 A.D.) by Ambrogio Lorenzetti; Paris Street, Rainy Day (1877) by Gustave Caillbotte; and Moscow (1911) by Mikhail Belyaevsky. Although cityscape paintings have declined in popularity during the past century, photographic cityscapes have become a popular genre of the art form.

Famous Artist: Paul Klee 1879-1940 →

Cabeza Con Bigote Aleman (1920)

Born on December 18, 1879, in Münchenbuchsee, Paul Klee was a German-Swiss painter, draftsman, printmaker, teacher and writer. He is regarded as a major theoretician among modern artists, a master of humour and mystery, and a major contributor to 20th century art.

Klee was born into a family of musicians and his childhood love of music would remain very important in his life and work. From 1898 to 1901 he studied in Munich under Heinrich Knirr, and then at the Kunstakademie under Franz von Stuck. In 1901 Klee traveled to Italy with the sculptor Hermann Haller and then settled in Bern in 1902.

A series of his satirical etchings called “The Inventions” were exhibited at the Munich Secession in 1906. That same year Klee married pianist Lily Stumpf and moved to Munich. In 1907, the couple had a son, Felix. For the next five years, Klee worked to define his own style through the manipulation of light and dark in his pen and ink drawings and watercolour wash. He also painted on glass, applying a white line to a blackened surface. During this time Klee paid close attention to Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting and became interested in the work of van Gogh, Cézanne, and Matisse.

In 1911, Klee met Alexej Jawlensky, Vasily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, and other avant-garde figures. He participated in art shows including the second Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) exhibition at Galerie Hans Goltz, Munich, in 1912, and the Erste deutsche Herbstsalon at the Der Sturm Gallery, Berlin, in 1913. Klee shared with Kandinsky and Marc a deep belief in the spiritual nature of artistic activity. He valued the authentic creative expression found in popular and tribal culture and in the art of children and the insane.

Klee’s main concentration on graphic work changed in 1914 after he spent two weeks in Tunisia with the painters August Macke and Louis Moilliet. He produced a number of stunning watercolours and colour became central to his art for the remainder of his life.

During World War I, Klee worked as an accounting clerk in the military and was able to continue drawing and painting at his desk. His work during this period had an Expressionist feel, both in their brightness and in motifs of enchanted gardens and mysterious forests.

In 1918, Klee moved back to Munich and worked extensively in oil for the first time painting intensely coloured, mysterious landscapes. During this time, he also became interested in the theory of art and published his ideas on the nature of graphic art in the ‘Schöpferische Konfession’ in 1920. Klee also became interested in politics and joined the Action Committee of Revolutionary Artists, an association that supported the Bavarian Socialist Republic. Like other artists at the time, Klee had envisioned a more central role for the artist in a socialist community.

In 1920, Klee was appointed to the faculty of the Bauhaus in Weimar where he taught from 1921 to 1926 and in Dessau from 1926 to 1931. During this time Klee developed many unique methods of creating art. The most well known is the oil transfer drawing which involves tracing a pencil drawing placed over a page coated with black ink or oil, onto a third sheet. That sheet receives the outline of the drawing in black, in addition to random smudges of excess oil from the middle sheet.

During his years in Weimar, Klee achieved international fame. However, his final years at the Dessau Bauhaus were marked by major political problems. In 1931 Klee ended his contract shortly before the Nazis closed the Bauhaus. He began to teach at the Düsseldorf art academy, commuting there from his home in Dessau.

In Düsseldorf Klee developed a divisionist painting technique that was related to Seurat’s pointillist paintings. These works consisted of layers of colour applied over a surface in patterns of small spots. His time in Düsseldorf however, was affected by the rise of the Nazis. In 1933 he became a target of a campaign against Entartete Kunst. The Nazis took control of the academy and in April Klee was dismissed from his post. In December he and his wife left Germany and returned to Berne.

In 1935 Klee developed the first symptoms of scleroderma, a skin disease that he suffered with until his death. Despite his personal and physical challenges, Klee’s final years were some of his most productive times. Several hundred paintings and 1583 drawings were recorded between 1937 and May 1940. Many of these works depicted the subject of death and his famous painting, “Death and Fire”, is considered his personal requiem.

Paul Klee died in Muralto, Locarno, Switzerland, on June 29, 1940. He was buried at Schosshalde Friedhof, Bern, Switzerland. A museum dedicated to Klee was built in Bern, Switzerland, by Italian architect Renzo Piano. Zentrum Paul Klee opened in June 2005 and holds a collection of about 4,000 work.

For more information, see the source files below. The MoMA, site has a great in-depth biography including information on his working methods.

Bronze: The History and Development of a Medium →

Rosetta "The Lion" Bronze 7" x 11.5" x 5.5" Edition of 100

Tin-based bronze came into existence late in the third millennium B.C. Bronze is a metal alloy that consists mainly of copper though other elements such as tin are added along with aluminium, phosphorus, and manganese. It is characterized by its hardness, but was known to be brittle. Its use became so widespread that the period of antiquity known as the Bronze Age was named for this metal alloy, a period of time particularly known for its skilled metalwork. Before bronze copper was the metal of choice, but the addition of tin gave way to the much stronger new metal.

Bronze was used to make weapons, tools, and armor, but it was also used extensively in the creation of art; and indeed, even functional bronze items were often treated to artistically rendered decoration. The earliest tin-bronzes (an earlier bronze was composed with arsenic) originated in Susa and other nearby cities of Mesopotamia. Trade helped nurture the production of bronze since copper and tin ores were seldom found in the same areas.

As an artistic medium, bronze was extensively used by artists and artisans. Bronze was famously employed in sculpture. An early example of bronze statuary comes from India’s Chola Empire in Tamil Nadu. Africa’s Kingdom of Benin famously produced bronze heads. The Greeks, Egyptians, and Chinese of antiquity are also revered for their sculptures as well as other bronze art works. The use of bronze became widespread and the Bronze Age chiefly lasted until 1200 B.C. Many cultures influenced bronze casting with advancements during this period which also increased bronze usage for artistic purposes.

Ancient bronze art is known for its great beauty. Many bronze artifacts were once used ceremonially especially in places like China. One early example of a Chinese bronze is a vessel that may have been created as early as 722 B.C. and depicts a pattern of interconnecting dragons. Other beautiful and intricately carved bronze vessels are some of antiquity’s best known works of art. As a medium, bronze allowed for great detail and sophisticated artistry.

Although iron eventually supplanted bronze in many industries, bronze remained an important art medium. In fact, some of the most famous bronze art works date to the artist Rodin who lived from 1840 to 1917. While the ancients knew of a wax process used to mold bronze, it has been lost to time, but the production of bronze art works has continued into the present making the most of new technologies. Contemporary artists continue to produce bronze objects of art in all manner of artistic styles.

Famous Artists: Anthony Van Dyck →

Self-Portrait

The Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck was born in 1599 and was famous for his Baroque works of art. His influence on English portrait painting would dominate style for well more than a century. As a court painter for King Charles I of England and Scotland, van Dyck excelled in portraiture, but was also famed for his work with watercolour and etching as well as his various genre paintings.

Born in Antwerp to a well-off family, van Dyck displayed artistic promise early on and was sent to study with the painter Hendrick van Balen by the year 1609. Within a few years he became an independent artist and set up a studio with his friend, the painter Jan Brueghel the Younger. In 1618 van Dyck was accepted as a member of the Painters’ Guild of St. Luke. He then became an assistant to Peter Paul Rubens and was revered as the master’s best student.

In 1620 van Dyck traveled to England to work for both King James I and James VI. At this point van Dyck demonstrated the influence of Rubens, but he also showed his influence from Titian. After a return to Flanders, van Dyck next journeyed to Italy where he studied the masters. He also became a popular portrait artist at this time. His most glorious success came, however, upon his return to England where King Charles and his wife sat for him nearly exclusively during his lifetime. He was paid handsomely and received many commissions due to his ease among the aristocracy as well as his talent. He became immensely famous for his paintings that showcased his cavalier garments and style.

In 1638 van Dyck married one of the queen’s ladies in waiting, the daughter of a peer. They would have one daughter. The artist also had a daughter by his mistress. He died in 1641 in England after returning ill from Paris. England’s Royal Collection contains the most famous collection of van Dyck paintings. However, the artist’s works are collected by the world’s most illustrious museums. Some of van Dyck’s most famous paintings include the Triple Portrait of King Charles I (1635-1636), Self Portrait with a Sunflower (c.1633), King Charles I (c.1635), Samson and Delilah (c. 1630), Elena Grimaldi (1623), Amor and Psyche (1638), Marie –Louise de Tassis (1630). His paintings, while famed for his cavalier style, were also influential for their subtlety of technique which profoundly influenced the subsequent century of English portrait art.

Oil Paint: The History and Development of a Medium →

As evidenced by the innumerable masterpieces exhibited on gallery walls of the most prestigious museums worldwide, perhaps it is the medium of oil that has created the most significant impact on the development of painting as visual art form. Painting with oil on canvas continues to be a favored choice of serious painters because of its long-lasting color and a variety of approaches and methods. Oil paints may have been used as far back as the 13th century. However as a medium in its modern form, Belgian painter, Jan van Eyck, developed it during the 15th century. Because artists were troubled by the excessive amount of drying time, van Eyck found a method that allowed painters an easier method of developing their compositions. By mixing pigments with linseed and nut oils, he discovered how to create a palette of vibrant oil colors.

Over time, other artists, such as Messina and da Vinci, improved upon the recipe by making it an ideal medium for representing details, forms and figures with a range of colors, shadows and depths. During the Renaissance, which is often referred to as the Golden Age of painting, artists developed their crafts and established many of the techniques that provided the medium of oil to emerge. The refinement of oil painting came through studies in perspective, proportion and human anatomy. During the Renaissance, the goal for artists was to create realistic images. They sought to represent all that was caught by an artist’s detailed eye, as well as capture and present the intensity of human emotions.

Giovanni Bellini’s work from 1480, “St. Francis in Ecstasy,” captures oil’s ability to create an accurate, complex composition with the soft glow of morning light and the detailed perspective of the natural landscape. Oil became a useful medium during the Baroque period, when artists sought to display the intensity of emotion through the careful manipulation of light and shadows. Rembrandt’s use of oil in his piece, “Night Watch,” from 1642, displays the concerns of the night watch with a dark, yet detailed background and the crisp brightness of the golden garments. In the mid-19th century, as painters explored new approaches and developed new movements, oil as a medium followed. In the 1872 painting “Impression, Sunrise,” for which the Impressionist movement was named, Monet used oil to provide an evocative view of the harbor, silhouettes and sun as reflections danced on the water. Into Modernism and beyond, oil has been used by artists, such as Kandinsky, Picasso and Matisse, to further their experimental approaches in the early 20th century.

Easily removed from the canvas, oil allows the artist to revise a work. With its flexible nature, long history and large body of theories, oil painting has created a most significant impact on visual art. New developments in oil paints continued into the 20th century, with advent of oil paint sticks, which were used by artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Anselm Kiefer. Since the Renaissance, the masters used oil to create works that continue to inspire, intrigue and delight, and today, artists continue to use this significant medium to express their visions, goals and emotions.

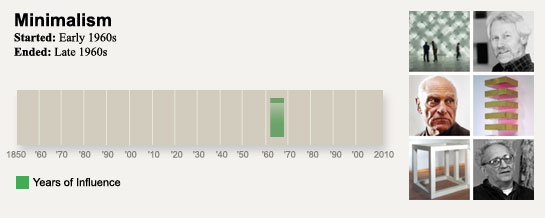

Minimalism Movement →

"A shape, a volume, a color, a surface is something itself. It shouldn't be concealed as part of a fairly different whole." - Donald Judd

The term "Minimalism" has evolved over the last half-century to include a vast number of artistic media, and its precedents in the visual arts can be found in Mondrian, van Doesburg, Reinhardt, and in Malevich's monochromes. But it was born as a self-conscious movement in New York in the early 1960s. Its leading figures - Donald Judd, Frank Stella, Robert Morris, and Carl Andre - created objects which often blurred the boundaries between painting and sculpture, and were characterized by unitary, geometric forms and industrial materials. Emphasising cool anonymity over the hot expressivism of the previous generation of painters, the Minimalists attempted to avoid metaphorical associations, symbolism, and suggestions of spiritual transcendence.

- The revival of interest in Russian Constructivism and Marcel Duchamp's readymades provided important inspiration for the Minimalists. The Russian's example suggested an approach to sculpture that emphasised modular fabrication and industrial materials over the craft techniques of most modern sculpture. And Duchamp's readymades pointed to ways in which sculpture might make use of a variety of pre-fabricated materials, or aspire to the appearance of factory-built commodities.

- Much of Minimalist aesthetics was shaped by a reaction against Abstract Expressionism. Minimalists wanted to remove suggestions of self-expressionism from the art work, as well as evocations of illusion or transcendence - or, indeed, metaphors of any kind, though as some critics have pointed out, that proved difficult. Unhappy with the modernist emphasis on medium-specificity, the Minimalists also sought to erase distinctions between paintings and sculptures, and to make instead, as Donald Judd said: "specific objects."

- In seeking to make objects which avoided the appearance of fine art objects, the Minimalists attempted to remove the appearance of composition from their work. To that end, they tried to expunge all signs of the artists guiding hand or thought processes - all aesthetic decisions - from the fabrication of the object. For Donald Judd, this was part of Minimalism's attack on the tradition of "relational composition" in European art, one which he saw as part of an out-moded rationalism. Rather than the parts of an artwork being carefully, hierarchically ordered and balanced, he said they should be "just one thing after another."

In New York City in the late 1950s, young artists like Donald Judd, Robert Morris and Dan Flavin were painting in then dominant Abstract Expressionist vein, and beginning to show at smaller galleries throughout the city. By the early 1960s, many of these artists had abandoned painting altogether in favour of objects which seemed neither painting nor sculpture in the conventional sense. For example, Frank Stella's Black Paintings (a series of hugely influential, concentrically striped pictures from 1959-60), were much thicker than conventional canvases, and this emphasised their materiality and object-ness, in contrast to the thin, window-like quality of ordinary canvases. Other early Minimalist works employed non-art materials such as plywood, scrap metal, and fluorescent light bulbs.

Many names were floated to characterise this new art, from "ABC art" and "Reductive Art" to "literalism" and "systemic painting." "Minimalism" was the term that eventually stuck, perhaps because it best described the way the artists reduced art to the minimum number of colors, shapes, lines and textures. Yet the term was rejected by many of the artists commonly associated with the movement - Judd, for example, felt the title was derogatory. He preferred the term "primary structures," which came to be the title of a landmark group show at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1966: it brought together many of those who were important to the movement, including Sol LeWitt, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris, Carl Andre, and Donald Judd, though it also included some who were barely on its fringes, such as Ellsworth Kelly and Anthony Caro.

The Minimalists' emphasis on eradicating signs of authorship from the artwork (by using simple, geometric forms, and courting the appearance of industrial objects) led, inevitably, to the sense that the meaning of the object lay not "inside" it, but rather on its surface - it arose from the viewer's interaction with the object. This led to a new emphasis on the physical space in which the artwork resided. In part, this development was inspired by Maurice Merleau-Ponty's writings on phenomenology, in particular, The Phenomenology of Perception (1945).

Aside from sculptors, Minimalism is also associated with a few key abstract painters, such as Frank Stella and, retrospectively, Barnett Newman. These artists painted very simple canvases that were considered minimal due to their bare-bones composition. Using only line, solid color and, in Stella's case, geometric forms and shaped canvas, these artists combined paint and canvas in such a way that the two became inseparable.

By the late 1960s, Minimalism was beginning to show signs of breaking apart as a movement, as various artists who had been important to its early development began to move in different directions. By this time the movement was also drawing powerful attacks. The most important of these would be Michael Fried's essay "Art and Objecthood," published in Artforum in 1967. Although it seemed to confirm the importance of the movement as a turning point in the history of modern art, Fried was uncomfortable with what it heralded. Referring to the movement as "literalism," and those who made it as "literalists," he accused artists like Judd and Morris of intentionally confusing the categories of art and ordinary object. According to Fried, what these artists were creating was not art, but a political and/or ideological statement about the nature of art. Fried maintained that just because Judd and Morris arranged identical non-art objects in a three-dimensional field and proclaimed it "art", didn't necessarily make it so. Art is art and an object is an object, Fried asserted.

As the 1960s progressed, different offshoots of Minimalism began to take shape. In California, the "Light and Space" movement was led by Robert Irwin, while in vast ranges of unspoiled land throughout the U.S., Land artists like Robert Smithson and Walter de Maria completely removed art from the studio altogether, and turned the earth itself into a work of art. This achievement not only further blurred the boundaries between "art" and "object," but reinvented the more conventional definitions of sculpture.

The significance of Michael Fried's attack on the movement continues to be discussed, and, to the extent that, as critic Hal Foster has put it, Minimalism forms a "crux" or turning point in the history of modernism, the movement remains hugely influential today. However, some critics have challenged the reputations of some leading figures such as Donald Judd: in particular, feminists have criticized what they see as a rhetoric of power in the style's austerity and intellectualism. Indeed, it is the legacy of the movements that followed in Minimalism's wake, and that are often canopied under the term "Post-Minimalism" (Land Art, Eccentric Abstraction, and other developments) that is more important.

Expressionism Movement →

"Everyone who renders directly and honestly whatever drives him to create is one of us." - E.L. Kirchner

Expressionism emerged simultaneously in various cities across Germany as a response to a widespread anxiety about humanity's increasingly discordant relationship with the world and accompanying lost feelings of authenticity and spirituality. In part a reaction against Impressionism and academic art, Expressionism was inspired most heavily by the Symbolist currents in late nineteenth-century art. Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch, and James Ensor proved particularly influential to the Expressionists, encouraging the distortion of form and the deployment of strong colors to convey a variety of anxieties and yearnings. The classic phase of the Expressionist movement lasted from approximately 1905 to 1920 and spread throughout Europe. Its example would later inform Abstract Expressionism, and its influence would be felt throughout the remainder of the century in German art. It was also a critical precursor to the Neo-Expressionist artists of the 1980s.

- The arrival of Expressionism announced new standards in the creation and judgment of art. Art was now meant to come forth from within the artist, rather than from a depiction of the external visual world, and the standard for assessing the quality of a work of art became the character of the artist's feelings rather than an analysis of the composition.

Key Ideas

- Expressionist artists often employed swirling, swaying, and exaggeratedly executed brushstrokes in the depiction of their subjects. These techniques were meant to convey the turgid emotional state of the artist reacting to the anxieties of the modern world.

- Through their confrontation with the urban world of the early twentieth century, Expressionist artists developed a powerful mode of social criticism in their serpentine figural renderings and bold colors. Their representations of the modern city included alienated individuals - a psychological by-product of recent urbanization - as well as prostitutes, who were used to comment on capitalism's role in the emotional distancing of individuals within cities.

With the turn of the century in Europe, shifts in artistic styles and vision erupted as a response to the major changes in the atmosphere of society. New technologies and massive urbanization efforts altered the individual's worldview, and artists reflected the psychological impact of these developments by moving away from a realistic representation of what they saw toward an emotional and psychological rendering of how the world affected them. The roots of Expressionism can be traced to certain Post-Impressionist artists like Edvard Munch in Norway, as well as Gustav Klimt in the Vienna Secession, and finally emerged in Germany in 1905.

Edvard Munch in Norway

The late nineteenth-century Norwegian Post-Impressionist painter Edvard Munch emerged as an important source of inspiration for the Expressionists. His vibrant and emotionally charged works opened up new possibilities for introspective expression. In particular, Munch's frenetic canvases expressed the anxiety of the individual within the newly modernized European society; his famous painting The Scream (1893) evidenced the conflict between spirituality and modernity as a central theme of his work. By 1905 Munch's work was well known within Germany and he was spending much of his time there as well, putting him in direct contact with the Expressionists.

Gustav Klimt in Austria

Another figure in the late nineteenth century that had an impact upon the development of Expressionism was Gustav Klimt, who worked in the Austrian Art Nouveau style of the Vienna Secession. Klimt's lavish mode of rendering his subjects in a bright palette, elaborately patterned surfaces, and elongated bodies was a step toward the exotic colors, gestural brushwork, and jagged forms of the later Expressionists. Klimt was a mentor to painter Egon Schiele, and introduced him to the works of Edvard Munch and Vincent van Gogh, among others, at an exhibition of their work in 1909.

The Advent of Expressionism in Germany

Although it included various artists and styles, Expressionism first emerged in 1905, when a group of four German architecture students who desired to become painters - Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Erich Heckel - formed the group Die Brücke (the Bridge) in the city of Dresden. A few years later, in 1911, a like-minded group of young artists formed Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) in Munich, after the rejection of Wassily Kandinsky's painting The Last Judgment (1910) from a local exhibition. In addition to Kandinsky, the group included Franz Marc, Paul Klee, and August Macke, among others, all of whom made up the loosely associated group.

The Term "Expressionism"

The term "Expressionism" is thought to have been coined in 1910 by Czech art historian Antonin Matejcek, who intended it to denote the opposite of Impressionism. Whereas the Impressionists sought to express the majesty of nature and the human form through paint, the Expressionists, according to Matejcek, sought only to express inner life, often via the painting of harsh and realistic subject matter. It should be noted, however, that neither Die Brücke, nor similar sub-movements, ever referred to themselves as Expressionist, and, in the early years of the century, the term was widely used to apply to a variety of styles, including Post-Impressionism.

Jean Arp: 1886 – 1966 →

plastron et fourchette shirtfront and fork

Born on September 16, 1886 in Strasbourg (then part of Germany), Jean (Hans) Arp was a pioneer of abstract art and a founding member of the Dada movement. After studying at the Kunstschule, Weimar from 1905 to 1907, Arp attended the Académie Julian in Paris.

In 1909, Arp moved to Switzerland where in 1911 he was a founder of and exhibited with the Moderne Bund group. One year later, he began creating collages using paper and fabric and influenced by Cubist and Futurist art. Arp then traveled to Paris and Munich where he became aquainted with Robert and Sonia Delaunay Vasily Kandinsky, Amadeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, and others.

In 1915, with the onset of World War I, Arp moved to Zurich, feigning mental instability to avoid military service. It is here where he met and collaborated with Sophie Taeuber, creating tapestries and collages, and whom he married in 1922.

In 1916, Arp became part of the founding group of the Zurich Dada artists. Their aim was to encourage spontaneous and chaotic creation, free from prejudice and the academic conventions that many believed were the root causes of war. For Arp, Dada represented the “reconciliation of man with nature and the integration of art into life.” At the end of the war, Arp continued his involvement with Dada promoting it in Cologne, Berlin, Hannover, and Paris.

Although Arp was committed to Dada, he also aligned himself somewhat with the Surrealists, exhibiting with the group in Paris exhibitions in the mid 1920′s. He shared their notion of unfettered creativity, spontaneity, and anti-rational position.

Arp and his wife also had close ties to Constructivist groups such as De Stijl, Cercle et carré, Art Concret and Abstraction–Création, all of which aimed to create a counterbalance to Surrealism as well as to change society for a better future.

In the early 1930′s, Arp developed the principle of the “constellation,” and used it in both his writings and artworks. While creating his reliefs, Arp would identify a theme, such as five white shapes and two smaller black ones on a white ground, and then reassemble these shapes into different configurations.

In the 1930′s, Arp began creating free-standing sculpture. Just as his reliefs were unframed, Arp’s sculptures were not mounted on a base, enabling them to simply take their place in nature. Instead of the term abstract art, he and other artists, referred to their work as Concrete Art, stating that their aim was not to reproduce, but simply to produce more directly. Arp’s goal was to concentrate on form to increase the sculpture’s domination of space and its impact on the viewer.

From the 1930′s onward, Arp also wrote and published poetry and essays. As well, he was a pioneer of automatic writing and drawing that were important to the Surrealist movement.

With the fall of Paris in 1942, Arp fled the war for Zurich where he remained, returning to Paris in 1946. In 1949, he traveled to New York where he had a solo show at Curt Valentin’s Buchholz Gallery. In 1950, Harvard University in Cambridge, MA invited him to create a relief for their Graduate Center. In 1954, Arp was awarded the Grand Prize for Sculpture at the Venice Biennale. Retrospectives of his work were held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in 1958 and at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, in 1962.

Jean Arp died June 7, 1966, in Basel, Switzerland at the age of 80. His works are in major museums around the world including a large collection at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Strasbourg.