Born on December 18, 1879, in Münchenbuchsee, Paul Klee was a German-Swiss painter, draftsman, printmaker, teacher and writer. He is regarded as a major theoretician among modern artists, a master of humour and mystery, and a major contributor to 20th century art.

Klee was born into a family of musicians and his childhood love of music would remain very important in his life and work. From 1898 to 1901 he studied in Munich under Heinrich Knirr, and then at the Kunstakademie under Franz von Stuck. In 1901 Klee traveled to Italy with the sculptor Hermann Haller and then settled in Bern in 1902.

A series of his satirical etchings called “The Inventions” were exhibited at the Munich Secession in 1906. That same year Klee married pianist Lily Stumpf and moved to Munich. In 1907, the couple had a son, Felix. For the next five years, Klee worked to define his own style through the manipulation of light and dark in his pen and ink drawings and watercolour wash. He also painted on glass, applying a white line to a blackened surface. During this time Klee paid close attention to Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting and became interested in the work of van Gogh, Cézanne, and Matisse.

In 1911, Klee met Alexej Jawlensky, Vasily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, and other avant-garde figures. He participated in art shows including the second Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) exhibition at Galerie Hans Goltz, Munich, in 1912, and the Erste deutsche Herbstsalon at the Der Sturm Gallery, Berlin, in 1913. Klee shared with Kandinsky and Marc a deep belief in the spiritual nature of artistic activity. He valued the authentic creative expression found in popular and tribal culture and in the art of children and the insane.

Klee’s main concentration on graphic work changed in 1914 after he spent two weeks in Tunisia with the painters August Macke and Louis Moilliet. He produced a number of stunning watercolours and colour became central to his art for the remainder of his life.

During World War I, Klee worked as an accounting clerk in the military and was able to continue drawing and painting at his desk. His work during this period had an Expressionist feel, both in their brightness and in motifs of enchanted gardens and mysterious forests.

In 1918, Klee moved back to Munich and worked extensively in oil for the first time painting intensely coloured, mysterious landscapes. During this time, he also became interested in the theory of art and published his ideas on the nature of graphic art in the ‘Schöpferische Konfession’ in 1920. Klee also became interested in politics and joined the Action Committee of Revolutionary Artists, an association that supported the Bavarian Socialist Republic. Like other artists at the time, Klee had envisioned a more central role for the artist in a socialist community.

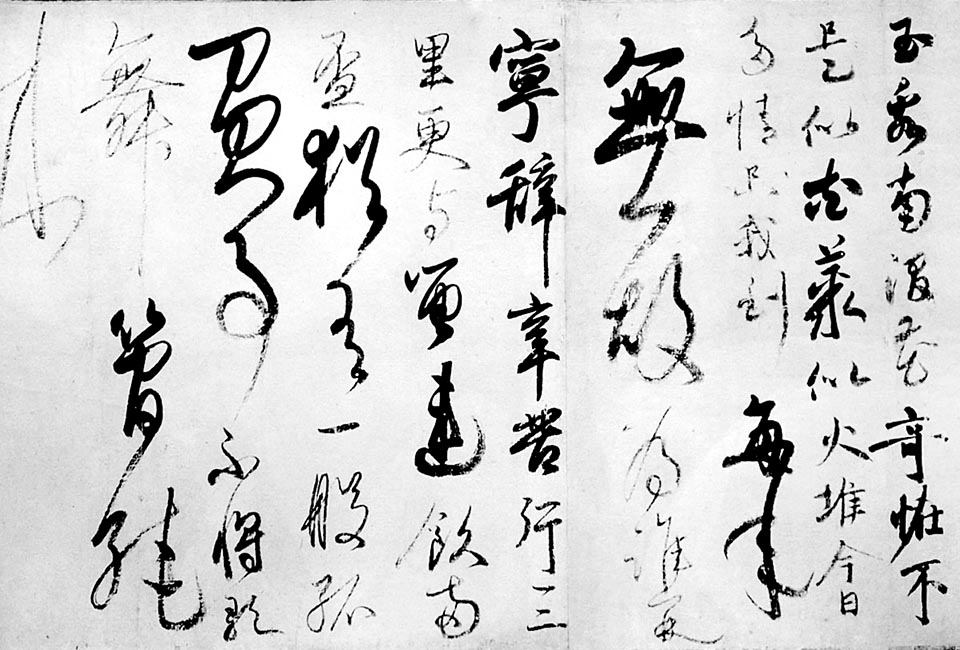

In 1920, Klee was appointed to the faculty of the Bauhaus in Weimar where he taught from 1921 to 1926 and in Dessau from 1926 to 1931. During this time Klee developed many unique methods of creating art. The most well known is the oil transfer drawing which involves tracing a pencil drawing placed over a page coated with black ink or oil, onto a third sheet. That sheet receives the outline of the drawing in black, in addition to random smudges of excess oil from the middle sheet.

During his years in Weimar, Klee achieved international fame. However, his final years at the Dessau Bauhaus were marked by major political problems. In 1931 Klee ended his contract shortly before the Nazis closed the Bauhaus. He began to teach at the Düsseldorf art academy, commuting there from his home in Dessau.

In Düsseldorf Klee developed a divisionist painting technique that was related to Seurat’s pointillist paintings. These works consisted of layers of colour applied over a surface in patterns of small spots. His time in Düsseldorf however, was affected by the rise of the Nazis. In 1933 he became a target of a campaign against Entartete Kunst. The Nazis took control of the academy and in April Klee was dismissed from his post. In December he and his wife left Germany and returned to Berne.

In 1935 Klee developed the first symptoms of scleroderma, a skin disease that he suffered with until his death. Despite his personal and physical challenges, Klee’s final years were some of his most productive times. Several hundred paintings and 1583 drawings were recorded between 1937 and May 1940. Many of these works depicted the subject of death and his famous painting, “Death and Fire”, is considered his personal requiem.

Paul Klee died in Muralto, Locarno, Switzerland, on June 29, 1940. He was buried at Schosshalde Friedhof, Bern, Switzerland. A museum dedicated to Klee was built in Bern, Switzerland, by Italian architect Renzo Piano. Zentrum Paul Klee opened in June 2005 and holds a collection of about 4,000 work.

For more information, see the source files below. The MoMA, site has a great in-depth biography including information on his working methods.